Tuesday 29th of November 2022

EASE TALKS n°4 – The energy costs crisis and its impact on the sport sector

The year 2022 was marked by great difficulties regarding energy supplies in Europe, because of the Russian invasion against Ukraine, the reduction of gas flows in different pipelines and the uncertainty of the markets. The gas market and the electricity market have been impacted by these events: they are submitted to unusually high prices. As a result, the wholesale electricity and gas prices rose tremendously during the summer. The increase of the electricity prices has been estimated over 200% for sixteen member states and above 100% for 9 member states between June 2021 and June 2022 (for more information on the European energy and gas markets, see the Eurostat reports here).

The European Union is currently working on different measures that aim at phasing out fossil fuel imports from Russia, increasing security of energy supply and supporting the energy transition. New measures are expected, on reducing demand for gas or electricity and reforming the market design of energy in Europe. All member states are also working on national measures to protect households and industrial consumers from this crisis and its consequences.

However, sport actors and employers have to face increasing energy costs. These higher expenses strongly impact their functioning and question their sustainability. As a consequence, sport activities face a great risk, as there already is a globalised fragility of sport structures, some of which still have to recover from the covid period.

Main risks and consequences of the crisis

The most immediate risk relies on high energy consuming facilities, such as swimming pools and skating rinks. The risk of closing of these facilities is present in many countries of the European Union: some facilities were closed in October 2022 in the Netherlands, in Slovenia, in Ireland, in Finland, in France, in Lithuania or in Belgium. This can easily be explained by the high maintenance costs of these infrastructures, that are directly impacted by the rise of energy costs: for instance, in Spain, clubs owning such facilities must face a rise of their energy costs up to 30% of their total costs. That’s why the risk of closure of skating rinks and swimming pools is present in Austria, in Poland, in Latvia or in Croatia and the proposition of closure of these infrastructures has been debated in Spain, in Germany or in Denmark, even if it has not been applied yet.

The question of the infrastructures can be extended to all the indoor sport associations, and more particularly to the clubs owning their facilities, as they directly have to pay for the increased costs. On the contrary, when facilities are held by municipalities or public bodies, the energy costs are moved to public authorities and this considerably eases the burden on sports associations, like it is the case for some sport structures in France or in Finland.

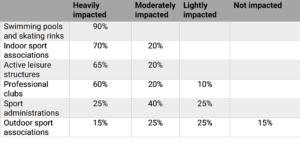

This economic and energy crisis can more largely have consequences on all sport structures: from a survey realised among 20 European countries, it appears that indoor sport associations, professional clubs and active leisure structures are the most heavily impacted by this crisis, but all sport structures are more or less impacted by this situation:

* These percentages have been calculated from the answers received from national authorities in 20 European countries.

This explains the risk of bankruptcy which is real for many sport structures in Europe: if their maintenance or energy costs rise too much, clubs won’t be sustainable anymore and there’s a great risk of closure for them. This fear is shared among various member states: according to a survey realised by the German Olympic committee, 40% of the clubs expect the energy crisis to have a strong impact and 6% even fear an acute threat to their existence, like the dissolution of the club. In Austria, the projections of Sport Austria indicate that there could be up to €1 billion of additional expenditure for the sport sector as a whole (sport equipment, sport facilities, sport services, medias, …)).

This risk of closure also comes from the specific functioning of the sport economic system: unlike other economic markets, clubs and associations cannot pass on the increased costs in the price of sports activities on customers, as this would mean an unbearable multiplication of the prices for participants.

Whereas it is still of great importance to ensure a stable and global sport practice, households also face a rise in the energy prices and the inflation. As a consequence, the share of their budget allocated to leisure, including sport activities and sport events, might be reduced. From a survey led by the Dutch Olympic Committee, 80.000 people already quit practicing because of higher fees and 250.000 people think of quitting sports if the costs rise any further.

This can impact both sport practice and sport events attendance. This indirect consequence of the energy crisis once again underlines the necessity to prevent a move of rising costs on the customers. Nevertheless, this creates a new difficulty for clubs and federations: whereas the organisation of sport events used to be a source of income for them, the impact of the inflation on the households’ spendings might also reduce their revenues.

The sport movement’s mobilization

Since the beginning of the crisis, many good practices have been spontaneously implemented by local sport structures, the most common measures being a lower heating, the reduction of the lightning or any other saving energy measures. These measures have been proposed by the sport structures themselves, but there’s very often a national coordination, with the definition of specific recommendations by governments or national sport organizations. For instance, the Portuguese government implemented an Energy Saving Plan 2022-2023 in place, with immediate measures to reduce the energy consumption of sport facilities.

However, as the energy prices continue rising, saving energy will not be enough to ensure the sustainability of sport structures. That’s why European sport employers agree that public action and state aids are necessary to help sport structures, as reducing the energy consumption is not efficient enough to face the growing energy costs crisis.

It appears that public action is very diverse from one country to another. The most common measures are cap prices on the electricity and/or gas markets or the implementation of public subsidies, compensations or loans. Discussions are also ongoing about a VAT reduction in countries such as Finland or Poland.

Depending on the country, actions are implemented at national or local level and can apply to sport structures or include more generally small associations or businesses, without regard for the specific sector they belong to. In countries such as Netherlands or Belgium, negotiations are ongoing between the government and the sport sector to obtain specific funds for clubs and associations this winter.

However, these mechanisms are not sustainable in the long term. The year 2023 might be a difficult period for sport structures, that will have to face the consequences of the inflation and the rising energy costs. In the meantime, the question of the energy consumption is becoming increasingly important and will be debated for the next years, as it generally questions the sport sustainability. For instance, the French ministry of sports set up a target to reduce the energy consumption of the sport sector by 10% in 2023 and by 40% in 2030. An energy efficiency plan has been published in October 2022 for sport structures, as a first step to meet these goals.

In this context, the issues of energy transition and infrastructure renewal, for a reduction of the energy consumption, appear as some long-term solutions to ensure a reduction of the energy costs for sport structures and a more sustainable sport system in Europe. The actors of the sport movement are starting to take up these issues, but it represents some very important costs for them. A structural reflection at the European level and the involvement of public fundings appear necessary, at least to encourage the renewal of sport infrastructures.

As a conclusion, each government is working on specific measures, but they don’t always apply to sport structures or are not specific to the sector: they may concern small business or corporate activities, that include sport associations or sport clubs. These public decisions often come with a more general preoccupation for sustainability issues, with general thoughts on the reduction of the energy consumption and the energy transition. Indeed, the energy-related issues are a daily concern for sport structures, but they go beyond the current crisis: sustainability and energy production will be central within the next years and issues related to the infrastructures’ renovation and the development of renewable energies will be of a growing importance for sport structures all over Europe.

However, in the upcoming months, sport structures will struggle to achieve economic stability, that’s why the economic importance and the social impact of the sport sector has to be underlined, as it has been proven during the closures due to COVID. As a consequence, there’s still a need to strengthen the relationship between the sport movement and the public actors, to highlight the social impact of sport and to secure some state or European aids for the most fragile sport structures.